13 Tips for Great Field Photos

With archives of more than 45,000 big-game trophies dating back to 1830, perhaps no organization sees more field photos, from wow to meh, than Boone and Crockett Club.

Trophy data is vital for conservation because it gauges species, population and habitat health. Outstanding field photos are a perfect opportunity for hunters to share this fact and demonstrate respect for the wildlife we hunt.

Click through these 13 tips that will help improve your field photo skills this season.

Home Page

Boone and Crockett Club ®

Pioneers of Conservation.

Our Legacy for Generations. ™

Play Hooky Ram – A B&C Audio Adventure

july 8, 2023

Wildlife Caught on Camera—Volume 10

july 8, 2023

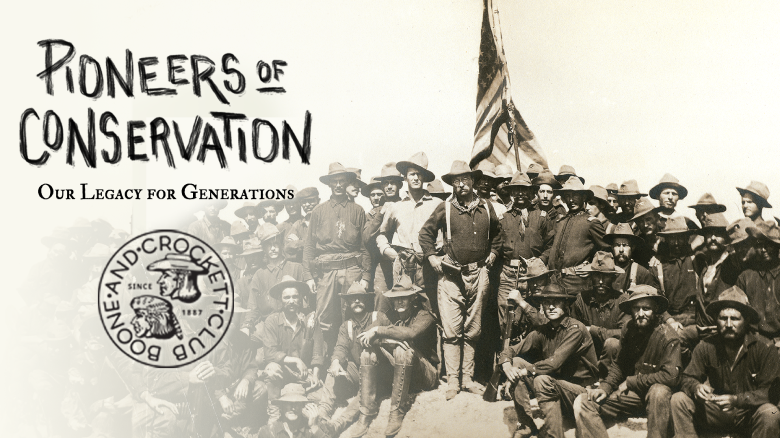

B&C Member Spotlight - Sasha Siemel

june 20, 2023

B&C Member Spotlight—George Anderson

july 8, 2023

The Best Present – A B&C Audio Adventure

july 8, 2023

Determined – A B&C Audio Adventure

july 8, 2023

The Ageless Winchester Model 70

july 8, 2023

Our Mission

It is the mission of the Boone and Crockett Club to promote the conservation and management of wildlife, especially big game, and its habitat, to preserve and encourage hunting and to maintain the highest ethical standards of fair chase and sportsmanship in North America.

Join the Club

The Boone and Crockett Club was founded in 1887 by Theodore Roosevelt, George Bird Grinnell and other avid hunters to prevent the further depletion of North America’s wildlife and wilderness. The Club’s earliest actions set in stone many of the laws and conservation efforts currently in place today. Giving birth to our nation’s National Parks, Wildlife Refuges, the return of robust and healthy big game herds across the continent, and every meaningful conservation effort since.